GOING BOLDLY AND STUMBLING BLINDLY INTO 1973,

Starlost has a unique reputation in Sci Fi history as ‘The worst SF series ever.’ It’s creator, Harlan Ellison wrote:

“In the hands of the inept, the untalented, the venal, and the corrupt, The Starlost became a veritable Mt. Everest of cow flop, and, though I climbed that mountain, somehow I never lost sight of the dream, never lost the sense of smell, and when it got so rank I could stand it no longer, I descended hand-over-hand from the northern massif, leaving behind $93,000, the corrupters, and the eviscerated remains of my dream.”

It was described as a ‘clusterfuck on a level rarely seen in the genre.’ Someone else said ‘to call the characters two dimensional was to exaggerate by one dimension.’ It was called ‘dull and flat.’ It was attacked for high school acting, terrible scripts, terrible sets. The book The World’s Best ST Television rated it as the wrost ever.

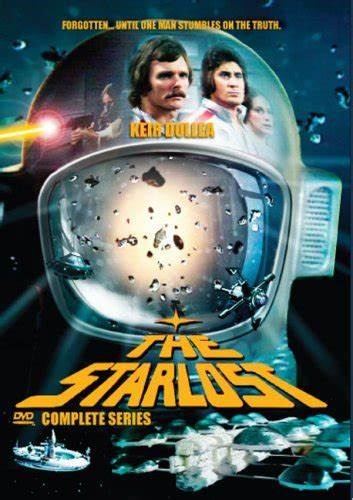

The series started off with high expectations. Created by Harlan Ellison an award winning SF and television writer known for work on both Star Trek and the Outer Limits, he had this vision for a ‘television novel’ that was literally decades ahead of its time, and anticipated programs like the Sopranos, Babylon 5, Breaking Bad and LEXX. It was produced by Douglas Trumbull effects producer for 2001: A Space Odyssey and Silent Running and starred Keir Dullea, star of 2001: A Space Odyssey as well as several classic Canadian films including Welcome to Blood City and Paperback Hero. The series featured award winning SF writer and editor Ben Bova as technical consultant.

Other notable names were guest stars John Colicos (Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica and such notable mainstream films as The Postman Always Rings Twice with Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange), Barry Morse (Space 1999 and the Fugitive), Sterling Hayden and Walter Koenig (Star Trek) and writers including award winning SF and Fantasy author Ursula K. LeGuin and Shimon Wincelberg (Star Trek and Lost in Space). They were going to use a ground breaking special effects technology called Magicam. Starlost should have been an SF fans wet dream, drawing as it did on people from the very best SF film, television and literature of the time.

Launched with fanfare, the plan was a season of twenty-four episodes. But after a strong initial showing, the ratings continually declined. Eventually, after sixteen episodes had aired, the series was cancelled, leaving the remaining eight episodes of the series unproduced.

I think most of its terrible reputation can be traced back to Harlan Ellison himself. Ellison, who recently died, but in his day he was one of the giants of Science Fiction, he wrote some of the best scripts for Star Trek and the Outer Limits, he wrote award winning short stories, he was a columnist, an editor, a legendary, over the top figure in the genre whose influence persists to this day.

He was also a giant asshat. He was never shy with invective, even against people that he worked with. He sued people at the drop of a hat. He was famous for little stunts to insult and belittle people, which, due to his talent and his reputation, everyone tried to overlook. His award winning Star Trek and Outer Limits scripts lead to him railing against and denouncing the producers for compromising his vision. I think that he eventually burned all his bridges for television writing.

On the Starlost project, reading between the lines, he seems to have been kind of a dick. He wasn’t the only problem, but he wasn’t helping much. His disenchantment reached a point where he walked off, insisted that he be credited as ‘Cordwainer Bird’ and then spent years nursing a grudge. Read any amount of Ellison’s nonfiction, and you get the impression that he spent a lot of his life nursing grudges.

Apparently, now and then, according to Ellison, friends of his would run across reruns of the show on television, they’d call him up and tell him they enjoyed it and it was terrific. Then he’d just blow up and shit all over them. I don’t know. If somebody did that to me, I think I’d stop calling them, ever. But Ellison shows little awareness.

Ironically, Ellison’s unending vitriol probably gave the series a life and notoriety that it would never have had without him. It only reached sixteen episodes, not nearly enough for syndication. The producers took ten of those episodes, and sandwiched them together into a sales package of five TV movies, which gave them a bit of a life on late night TV on independent stations.

In addition to his widely read memoir, Ellison also submitted and won an award for the original script, and wrote with, Edward Bryant, a novel ‘Phoenix Without Ashes.’ Ben Bova also got into the act with ‘Starcrossed’ a sci fi novel loosely based on his experiences, as well as other novels using the premise of the series. But while these made their own small contributions to the ‘legend’ they didn’t really help to create or perpetuate it.

Really, without Ellison’s nonstop harping, it would have been forgotten. It would have just ended up vanishing into obscurity.

But here’s the thing. I don’t actually think it was that bad. It wasn’t Star Trek. It wasn’t typical American television, not American action adventure sci fi. But maybe it didn’t have to be. And in many ways, I think it’s a fascinating example of Canadian sensibilities in Science Fiction. It reflects Canadian themes and values, Canadian ideas. I can see why it didn’t fly well in the US. But I think its actually worthy of attention, respect, perhaps even academic study.

A LITTLE BIT OF BACKGROUND, THE SERIES PREMISE

You’ve probably never heard of it. This is a show that dates back to 1973. Here in the post-Blade Runner world of 2020, Starlost was almost fifty years ago, you probably have no idea what I’m talking about.

That’s okay. Let me give you a little background. Starlost was a syndicated science fiction television series, started by an American television producer named Robert Kline. Kline had worked for 20th Century Fox, but he wanted to branch out. He got Ellison to do a proposal, then he took it to the BBC. The BBC turned it down, it eventually ended up in Canada,

Here’s the premise: Cypress Corners is a backwards religious colony, Hutterites, or Mennonites or Amish or something. They wear homespun clothes, all the men have beards and hats. They all take it very seriously. But there’s a young farmer named Devon who gets in trouble with his questions and his disrespect, also he’s upset that his girlfriend, Rachel, is being married off to his best friend, Garth. Eventually, the Elders just decide to stone him to death. Devon escapes…

Then it gets strange, Devon, fleeing the colony, discovers that he’s not in the world at all. The religious colony, which is the only world he’s ever known, is just a dome on a gigantic generation ship, the Ark, with dozens of domes. This is pretty mind blowing, but it gets worse. It turns out that for the last 400 years, no one has been piloting the Ark, it’s been drifting aimlessly through space, and aimed straight at the heart of a star.

Devon, accompanied by his fellow Cypress Corners refugees, Rachel and Garth, form an awkward love triangle as they set out on a quest to save the Ark, or to find someone on this vast ship who can help them save it. Along the way, the trio go from Dome to Dome, encountering new societies, some primitive, some advanced, and make contact with the remnants of the ship’s control systems. Along the way, they encountered aliens, got shrunk down to microscopic level, encountered medical drama, dealt with space cops and killer bees. Some of it was cool, some of it was ridiculous, the usual tropes of 60’s and 70’s sci fi television.

It was part of that peculiar generation of oddly dystopian science fiction movies and television series that occupied the landscape between Star Trek, The Original Series in 1969, and Star Wars in 1977. There was Space 1999, Logans Run, Planet of the Apes, Genesis II, and a few others. The running theme seemed to be people finding themselves in a post-apocalyptic situation, and basically going from adventure to adventure, meeting new people and new situations, and trying to survive. There was no more ‘to Boldly Go Where No man Has Gone Before,’ rather, the heroes were lost and kind of screwed and just trying to get through the day, instead of ‘going boldly’ it was ‘stumbling blindly into a new mess.’

Oddly, many of these series seemed to draw their inspiration from the Fugitive, 1963-1967. In this series, It’s a good formula, because it keeps the character moving. New situations, new cast every week. It seems to have been popular with sci fi series because it gets you around the problem ‘If things are fine in the future, why leave?’ It wasn’t restricted to sci fi, the 80’s series ‘A-Team’ used the same formula.

But in Sci Fi, it seemed to come out fairly dystopic. Over and over, the protagonists were lost. They had no home, there was nothing to look back to. Instead, they stumbled haplessly into one crisis after another, either personal danger or a damaged society. Even if they won the battle, succeeded in saving everyone, it was all gone, because they’d have to move on. All they had was some forlorn hope of going home, or more realistically, trying to find a safe place to start over. It wasn’t much acknowledged in the episodes, but my god, the premises were depressing.

The contrast with earlier science fiction is startling. Star Trek wasn’t unique. Look at Destination Moon, 2001, the space operas of the era, it’s optimistic. There’s faith in the establishment – The Federation, Starfleet, the Army, the Navy, the Hospital, Scientists, the Government – these were trustworthy, they were working for us, we could rely on them. The protagonists represent the establishment, they cooperate, and they defeat the menaces, overcome the challenges.

But then in the decade between Star Trek and Star Wars, sci fi got dark. It was a sign of the times. The Vietnam war was going on, and it had become dark and unpopular. There had been the Pentagon Papers revealing that the government lied about Vietnam. Watergate was going. We would fall into the Oil/Energy crisis, Inflation, Stagnation. The world seemed to have gone off the rails. We couldn’t trust government, we couldn’t trust authority. There was no clear direction forward, the future was no longer bright and benign.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes ends with the world destroyed, then next Apes movie ends with the deaths of the ape protagonists. Silent Running was a movie about an environmentally devastated earth sending the last forests into space. Welcome to Blood City was an early Cyberpunk story, where, once the hero realizes he’s in virtual reality, goes simply runs away. Even the positive stuff seems to be dark, the future wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

It wasn’t just sci fi that was dark. Everything was bleak – in horror, this was the era where the monsters won. Where Count Yorga eats the virgin, where the zombies wind up eating the last human, the ghosts get their victims. Both popcorn action movies and serious dramas tended to end up in bleak places, this was the era of the Deer Hunter, Midnight Cowboy, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. It just wasn’t a fun time, and people reflected that in the art they produced.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF STARLOST, GOIN’ DOWN THE ROAD TO OUTER SPACE

For a long time, it was Canada’s only bona fide Sci Fi series (Actually, in the 1950’s the CBC had produced Space Command featuring James Doohan, a low budget space opera in the tradition of Tom Corbett and Space Patrol).

It wasn’t originally Canadian. Both Ellison and Kline were Americans, Trumbull was British. Dullea was an American, notwithstanding his preference for starring in a lot of Canadian and British productions. It wasn’t even intended to be, they tried the BBC first.

It just ended up here. Conceived in 1972, Starlost was produced in 1973 by the CTV network in Canada, for syndication to both the fledgling Canadian network and for American syndication.

It’s very clear that Starlost didn’t start as a Canadian production. At best, looking at all the sources, it seems like the real genesis of the series begins with Fox TV executive named Kline. hooking up with either Doug Trumbull or Keir Dullea, in England.

Both men were identified with science fiction, were reputable as artists and most importantly were bankable, from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Dullea as the star, Trumbull as the special effects maven. Trumbull had also gone on to produce the less successful but still impressive Silent Running.

It seems reasonable to assume that one brought the other on board, either directly through contact, or simply by allowing the use of their name to convince the other that the project was worthy. It isn’t at all clear when either man entered the project, but indirect evidence suggests that one or both probably preceded Harlan Ellison’s involvement.

Harlan Ellison was brought in by Kline to develop a premise and write the bible. At that point, the series is being pitched to Harlan as ‘the fugitive in space’ which implies that Kline actually had his star lined up. Kline tells Ellison that the series was to be shot in England. Dullea is living in England and refuses to work in the United States. This suggests that Dullea and possibly Trumbull had committed to the project even before Harlan showed up.

Ellison fleshed out the spare premise of ‘fugitive in space’ into the Starlost in a ten minute free associating monologue delivered into a tape recorder. This became the foundation of the series, with Ellison to be credited as creator and head writer.

Ellison then drags in Ben Bova as a technical consultant, and tries to enlist a group of Science Fiction writers, including Ursula K. LeGuin, Philip K. Dick, Frank Herbert, Thomas M. Disch and A.E. Van Vogt. I like the idea, but I’m not sure it would have worked, writing a television script is a different skill than writing a novel or short story, writers don’t necessarily bridge the gap. i think in the end, only LeGuin’s story made it in.

The original plan was to take it to the BBC in some sort of co-production arrangement, but apparently the BBC turned them down. ITV, the big private British network was overcommitted, and in particular, was already wrestling with its own space opera series, UFO/Space 1999.

Now, we don’t know how the series comes to Canada. Ellison records it only as yet another example of the Producers treachery and perfidy.

It seems more likely that the connection was Dullea again. Dullea was apparently make or break for the project, sufficient that they were willing to shoot in England to accommodate him. Dullea had already made several movies in Canada, ‘Welcome to Blood City,’ ‘Paperback Hero’ and was literally thought of as a Canadian actor. Back in the day, I was shocked to discover that he wasn’t Canadian. Although Dullea refused to shoot in the United States, he was quite comfortable working in Canada.

In Canada was CTV, a fledgling private network just beginning to look at developing its own programming. To them, Starlost must have seemed like a godsend. A project partly funded already by Fox, a marketing plan ready to go, big names in SF one of whom was simultaneously a big name in Canadian cinema, the closest thing we had to a Canadian movie star. Of course, they would jump right in.

There were even some advantages for the American backers to committing to Toronto. For one thing, it was literally a short plane ride to either New York or Los Angeles, a hop and a skip, rather than a transcontinental or transoceanic flight. Proximity seemed to offer advantages in terms of access to studio executives, markets, technical crew, actors and writers.

At this point, Norman Klenman is brought in. Klenman was a Hollywood screenwriter, born in Brandon, Manitoba, in 1923, growing up in British Colombia, and still maintained Canadian citizenship. He wound up writing four episodes, and apparently doing heavy rewrites on another four. Klenman also became the defacto script supervisor or editor and responsible for something like continuity.

Ellison saw the introduction of Klenman as a deliberate betrayal, and in his article portrays Klenman as a generic Hollywood hack. An unctous nobody who tells Ellison that he ‘doesn’t understand this science fiction stuff.’

I’m inclined to be more sympathetic to Kline and Klenman on this point than Ellison is. By its nature, television productions are fluid mediums, and the structuring of Starlost really does make it seem like Kline was putting it together like a house of cards.

Interestingly, after I’d written the original version of this essay, it ended up with Norman Klenman and he looked me up. He was kind enough to chat with me, and he had these comments. If he’s still around, I hope that he won’t feel I’m out of place…

“Harlan was a fellow member of the Writers Guild of America (west). I was also a member of the Hollywood screenwriters guild, which was absorbed by the WGA. Many of the greatest old screenwriters were still members in the seventies. I felt like an idiot with my half dozen credits. Some had 30, 40, 50 or even 60 major crcdits from the 20s to the 70s! Fine mentors too.

“Harlan did have some talent, but was also so self-aggrandising even fellow members could barely suppress their laughter.

Anyway it was quite an adventure with the cantankerous Harlan Ellison. I recall getting a call in Los Angeles to come help old friend Bill Davidson (producer), but felt it only right to check first with Harlam, whom I had heard of. Was met with a tirade. He was boiling.

When I got to Toronto, I found Bill Davidson and his assistant Ed Richardson in a panic. Sked about to begin and they hadn’t a script to shoot.

Harlan had written the bible of Starlost and skedaddled. There was not a script completed nor even in halfway form. Not a trained writer anywhere nearby. Bill handed me the pilot that Harlan had pasted together incomplete of course. Embarassed. I read it and saw why. It’s unshootable, said Bill. I agreed.

The worst sin of Harlan: he wrote a strange plan of separate distinct “pods” of the Starlost space ship, rural 19th Century religious in style. And boring as hell. There was no character, no development in the bible, no screen action. No linkage. No jeopardy. No notional line.

….

Much later, maybe two decades later (1990’s), Harlan wrote me a poison pen letter, which found me retired on Salt Spring Island off the coast here. Things must still have rankled. I just folded the thing up and mailed it back to him.

Harlan, I said, life is short. You wouldn’t want this kind of thing to turn up after your time runs out. And thought that the end of it.

So darn it, I got another letter from Harlan, still miffed, only slightly mollified, but still pissed. He Included the poison pen letter I had just returned him!” (January 22, 2010)

So… twenty years later, Ellison was still nursing his grudges, and writing hateful ranty letters. I don’t think that speaks well of him.

[In hindsight, I suppose I missed an opportunity here. I was emailing with one of the core creative people of the series – he had literally written half the episodes, had been script editor and continuity over the whole thing, he’d worked with the writers, the directors. If Ellison had framed the basic concepts, and Trumbull done the special effects, Norman Klenman really was the guy that shaped the series.

Maybe I should have taken advantage of that, conducted a full correspondence, talked about the whole series, about each of the stories, his vision, the ideas and themes of each episode, the decisions, the contributions. It feels like such an irreplaceable opportunity. And I let it pass.

To be fair, in the previous few months, my marriage had failed, I’d been in a near fatal rollover, a close encounter with a hungry bear, I’d had my home invaded and been held at gunpoint by police, had quit my job, left my home, and was now living in a bedbug infested, third floor walkup, trying to restart my career and… my life. It wasn’t a happy time, and I was a little worn out.

And honestly, previously I’d spent years working on a LEXX book, which had failed and left me badly burnt. The Starlost essay had been around for a couple of years, it too had failed. I was a little burnt out. Norman’s emails were a welcome surprise, but I just wasn’t in shape to even think of this.

Then again, this was 2010. Norman was 87 year old. Starlost had been 37 years previous for him. I think he was tickled to run across my essay, but it was ancient, ancient history for him. I’m not sure he would have been up for detailed discussions.]

One thing that Kline couldn’t have counted on, back when they were looking at London, were the Canadian Content requirements. Coming in at the height of the Canadian nationalist tide, the Federal government had decided that Canadian culture demanded its own film and television industry.

So it created tax incentives, and tax credits, it supported the industry in various ways. The government was unwilling to stand by and simply allow an embryonic film and television industry to be immediately co-opted and colonized like so many other industries. It worked!

The whole tax shelter thing for movies, for instance, really took off. Canada went from producing three movies a year in 1973, to sixty-six a few years later, the US was producing eighty. Of course, most of the films produced under the tax shelter were unwatchable. But the fact remained that pushing cultural industries was a big part of the agenda.

One of the most important components of pushing a Canadian nationalist agenda in culture was enacting content guidelines or requirements for Canadian talent, writers, actors, directors. The idea was simple – the government was prepared to help subsidise film or television produced in Canada. But it had to be by Canadians. American talent coming up just to make a quick buck, cash some cheques and fly home was just not on.

So productions set in Canada had to use Canadian talent – it didn’t all have to be Canadian talent. But there had to be some – at least some of the stars, some of the supporting actors, some of the behind the scenes talent had to be Canadian.

‘Hollywood Canadians’ were a staple in many Canadian productions of the 70’s and 80’s.

Basically, you needed Canadian talent, but you also needed trained crew and recognized film actors, not a lot of either was to be found in Canada.

The solution was to seek out expatriate Canadians, like Norman Klenman, working in L.A., looking for actors or writers who were established and working in the American market, but who still held Canadian citizenship. There were a lot of Canadians who had gone to Hollywood to make their fortune – Lorne Greene and William Shatner in front of the camera, people like Klenman behind the camera. Attaching these people to a project guaranteed you a degree of name recognition and production credibility. Obtaining such people were vital to accessing Canadian funding and tax grants for the production.

Selling the whole thing, being able to offer a credible package, seemed to rest on a handful of personal commitments, from Dullea, Trumbull and even Ellison (although I am not entirely certain how critical Ellison himself was. To the extent that any writer/creator would be considered crucial though, Ellison at this time and place was probably the man. On the other hand, his notion of his own role was probably exaggerated.). In short, he was trying to offer a science fiction package, and its success or failure to investors or producers depended on his ability to add a collection of big names in the genre.

Its possible that Kline was just another hack film and television producer looking for his big ticket. There’s probably some truth to that, but then again, that could be said with some degree of justification for Roddenberry or even Straczynski.

Alternately, it might even be that Kline was a science fiction buff of sorts, and that he genuinely wanted to do something impressive in the genre. Or it may simply be that having found himself in the genre, he made a sincere commitment to look for the best, rather than just sign on any old collection of hacks.

Certainly, Ellison has strong feelings about Kline and his conduct. But looking objectively at the events of the time, even in light of Ellison, I find it difficult to condemn the man outright.

My best guess is that it was an issue of sales. Kline was literally selling a song, and to make the song credible, he had to literally build a series of commitments, each one locking into the other, until finally, there was a package.

Consider the project as being like a school of fish that Kline had all persuaded to swim in one direction. One fish swimming away might cause others to lose confidence, too much of a delay, might cause some of the fish to lose confidence, if too many fish moved away, then the project failed. Quite often in film and television, that’s how it works. It’s an incredibly expensive proposition, and putting it together is like building a house of cards.

Kline was in an unenviable position, because some of the fish came to the table with demands. Dullea wouldn’t work in the United States. Ok, that was the bottom line. Without Dullea or another actor of equivalent stature the project collapsed. I think its worth remembering that Dullea was a screen actor and that there was much less overlap back then. For a movie star to go into television was not a step up. So it was important to cater to Dullea. England was a first choice. When England didn’t work out, Kline had to scramble to find an acceptable substitute location.

Kline, I don’t believe, ever had the option of waiting. The project simply couldn’t sit on ice. Six months or a year later, all the fish would have swum off and the the project would be dead.

Kline simply couldn’t afford the writers strike, although it looks like Ellison forced him too. Literally, the project was always teetering on the edge of collapse, too long a delay, the wrong person pulling out at the right time, and the whole thing fell apart.

Kline didn’t invent Dullea’s idiosyncratic and uncompromising demands not to shoot in the US. Kline certainly didn’t create the writers strike. And he certainly didn’t invent the Canadian content rules that he had to contend with, and there was no way for him to predict any of these things. All of these things were just things happening to the project that he had to cope with, and Ellison was simply the one damned thing after the other.

For his part, I think that Kline was forced into a compromise. Dullea, Ellison and Trumbull were a trinity of names he needed to keep associated with the project at all costs. At the same time, Canadian content requirements meant he needed to bring in someone like Klenman. He was forced to try to balance Klenman and Ellison and to hang onto Ellison at all costs.

This may explain a lot of what’s going on in Ellison’s article, the bizarre and sneaky maneuverings that Kline was pulling, attempting to seduce or intimidate or bribe Ellison into completing his work. It’s just not as evil or toxic as Ellison makes it out to be.

I certainly don’t condone these actions. But by this time, its clear from reports of Ellison’s work on Star Trek or on the Outer Limits indicated he was more than a little bizarre and hard to get along with himself. He appears to have developed a reputation as a passionate but quirky and cantankerous writer. I’m not inclined to get into ‘he said/she said’ debates, but I think reading Ellison’s own writing he himself admits he’s not the easiest person to get along with. Ellison is both uncompromising and an idealist, and neither of those qualities is particularly fitting for a project like this where the watchwords were compromise and flexibility.

On the other side of the coin, Ellison’s invective may not be entirely unjustified. Bova quit in disgust, as did Trumbull. Dullea seems to have come out of it with a certain amount of frustration and bitterness. It does seem like no one who was involved with the project came away all that happy.

The project seems filled with strong prickly personalities whose ambitions far exceeded the reasonable scope of what they could do in what was inherently a marginal production. One by one, they seemed to be poisoned by the endless adjustments and compromises and either backed off or dropped away.

Certainly there were no shortage of compromises demanded by the series. The first problem, and one which dominates any production, is money. Starlost was not a network production, rather, it’s financing seems to have been a shaky house of cards, partly funded by Fox, partly funded by CTV, partly funded by Canadian cultural subsidies and partly funded by syndication, it remained very much a shoestring production. The budget averaged about $100,000 per episode, which was low for television, even then, and incredibly low given the production demands of a science fiction series.

This can be seen in the decision to shoot with videotape rather than film, or in the visible poverty of the sets and production design. The sets and models are frequently threadbare, in some episodes set are dressed with 1970’s office furniture straight out of an Eaton’s showroom. Space suits feature winter gloves and boots from Zellers department store. You can see cost cutting everywhere, continual re-using of props and set pieces. The Robot in Return of Oro was borrowed from someone’s promotional campaign. The explorer ship in The Alien Oro has a lot of obvious plywood in its DNA.

There were other problems. Video was at the time a largely untried medium, new and not quite perfected, which was perhaps not up to the job it was being asked to do. Trumbull had come up with a ‘Magicam’ effects system, but that failed entirely. The production crew and supporting actors, mostly Canadian, were fairly inexperienced and completely unused to a production of this sort.

Added to all this were the rigours of shooting episodic television. A movie is a thing in and of itself. Generally, a movie is not bound to a demanding schedule, but rather, at Dullea and Trumbull’s levels at least, there was a certain luxury of time. One might take twenty or thirty days for principal photography, weeks for second unit photography, more weeks in editing and post production. In contrast, television worked to a delivery schedule, and the demands of television required that episodes basically be shot in a week to ten days. A film is a project, but a television series is an assembly line. Sixteen episodes of Starlost were the equivalent of eight feature films, but were probably produced in less time and with dramatically less money than 2001: A Space Odyssey or Silent Running.

Both Dullea and Trumbull were film people, and were notable as high strung artists in their crafts, completely unused to the demands of episodic television. In particular, there’s evidence that Trumbull had some trouble initially with deadlines, since some of the early promotions for Starlost actually recycled his footage from Silent Running. Trumbull, for his part, probably had some honest grievances with the medium of video, notwithstanding his Magicam.

Ultimately, what we had was a chronically underfunded production peopled largely by people who were foreign to the medium. With the exceptions of Kline and Klenman, practically everyone else, Dullea, Trumbull, Bova and the Canadian production crew were in, one way or another, fish out of water. Under the circumstances, their problems and grievances probably are not surprising.

Ben Bova, the technical consultant for the series who quit in disgust, wrote a book called the Starcrossed, in which he described the weasel as Canada’s national animal, and depicted Toronto as an endless wasteland of grey prefabricated concrete. So, we can assume he wasn’t a big fan of the maple leaf.

Perhaps no one was happy. Starting with Ellison, through Trumbull, Dullea, Bova, there’s a sense of great expectations crippled by the simple realities of production, and perhaps an understandable lingering bitterness.

Oddly, and quite surprisingly, the show was actually successful. In Canada, it was the second highest rated program during it’s run, and the highest rated drama. In the United States, its ratings were actually quite good. I’d always thought that it died of lack of interest and lack of viewers, but it turns out that what killed it was Fox pulled its funding.

Without Fox’s participation, the funding structure fell apart, and everyone went home. So it turns out, it wasn’t ratings that killed the show, just the usual corporate politics.

TAKING THE SHOW TO THE GREAT WHITE NORTH

Interestingly, Bova is quoted in the book TV North, “What really surprised me is that there was a great deal of national chauvinism on the set. I was a ‘Yankee.’ For the first time in my life, I heard phrases like ‘the flea knows how to live with the elephant.’”

Ben Bova’s quote is just a throwaway line. But I think it’s significant.

This is what hit him in the face: Canadian nationalism. That’s what startled him, it was right there, in his face. It was actually there, on the sets, among the production crew, the directors, the writers. It was there.

And more, Canadians were watching, it was the highest rated drama in English Canada during its run. So maybe it was saying something meaningful to Canadians.

The Canadian overtones of the series pose a challenging problem: Obviously, the concepts weren’t originally created by Canadians, or created in Canada, or even created with Canada in mind. Let’s face it, Harlan Ellison, Ben Bova, Doug Trumbull or Kline aren’t Canucks by any stretch of the imagination. Yet, despite this, the series does seem to have resonances to the Canadian experience. Why is this? How could this be?

Perhaps the resonance, on some level, lead to the series being adopted by Canadians. On the one hand, this seems ridiculous. Let’s face it, CTV was looking for a programming opportunity, if the Starlost package had arrived as a celebrity golf sitcom rather than a sci fi series, they would have gone with it. And they’d have gone with any kind of sci fi or adventure premise, if that had been offered. The series more or less fell into our laps after being largely passed on in both the US and Britain.

But, on the other hand, it didn’t fly in the United States. The American backers and syndication stations were never more than lukewarm to the series concept (or else, Dullea or no Dullea, it would have been made in the US) and certainly American audiences never got into it. The British apparently turned it down flat. Obviously, there were commercial and political reasons for the lack of interest of prospective British and American partners.

But I’m willing to speculate that one of the reasons the Starlost wasn’t produced in these countries was that really, it was alien to their national mythologies. It didn’t ‘grab.’

The pivotal American space operas of the sixties and seventies were about their mythology as a frontier. Star Trek said it explicitly when it called space ‘the final frontier,’ and when Gene Roddenberry called it ‘wagon train to the stars.’ Lost in Space is simply a pioneer drama, Little House on the Prairie done stupid.

Even the quest series that bore a resemblance to Starlost, like Logan’s Run, Planet of the Apes or Roddenberry’s failed Genesis II/Planet Earth series pilots were more about the frontier. Unlike Starlost, these unknown communities and strange new worlds weren’t visibly seen as tied together but existed as separate continents or islands, waiting to be discovered, and just as easily abandoned and forgotten.

On the other side of the ocean, Britain’s principal SF of the day reflected its perception of itself as an Island nation, apart and solitary, whether in Doctor Who, Space 1999, or the Gerry Anderson productions. The approaches differed. The early Gerry Anderson shows were optimistic excursions, the island dealing with a variety of foreigners, but confident of its place in the world. In Space 1999 it was an island in hostile seas to reflect the bleaker times of the seventies, but still, Moonbase Alpha was an island.

Starlost doesn’t relate to either of these national themes. That doesn’t necessarily leave us with Canada as the only default. Several other countries had live film and television establishments. The Italians, for instance, were making waves with their spaghetti westerns and even helped co-produce the second year of Space 1999. The Germans co-produced, with Britain, a 1970’s series called Star Maidens, and could have been prospective partners. Even the French might have been players. Certainly Trumbull and Dullea were physically much closer to Europe.

On the other side of the hemisphere, Japan had experimented with co-productions with the US, and had produced viable sci fi movies and TV series. Even Australia might have been a potential candidate to produce a series. In short, even with the US and Britain out, there were no shortage of nations that might have gone into a co-production like the Starlost in the early seventies.

It wound up in Canada, arguably as a result of a series of coincidences and opportunities, but also partly because the premise and themes some levels, I think it resonated to Canadians. Canadians could look at the basic premise, and it said something to them.

Starlost was meaningful for Canadians in a way that it wasn’t for Britain or the US or other nations. Sitting here in our collection of autonomous provinces, loosely bound, oblivous and hostile to each other, drifting along without apparent direction or leadership, on a possible course to destruction, in danger of becoming an American satellite, we’d look at the Starlost and for some reason, we could relate.

The notion of three rustics leaving their isolated backwoods countryside to seek out the center where power and control is, seems vaguely reminiscent of the Canadian classic ‘Going Down the Road’ from 1970, in which a trio of naive maritimers head for central Canada, looking for a future.

Of course, it’s also reminiscent of the quest for sanctuary in Logan’s Run, or any number of endless Fugitive type films and TV series. The notion of a hero, or even a trio who go on a quest certainly precedes ‘Going Down the Road’ by a few thousand years.

And yet, reading Ellison’s bible for the series, we find that the character of Garth was originally to be the hunter. He was going to be a dramatic element, like Francis in Logan’s Run, or Detective Javert in the Fugitive, always pursuing, usually one step behind, a constant danger a reluctant ally, an easy source of tenstion and conflict.

Somehow, this concept of Garth vanished and he became one of the trio. This obviously blew a lot of obvious opportunities for dramatic tension and arguably wasted the character, since as one of the group he didn’t have a lot to do most of the time. There’s an evolution here which is hard to account for or explain in formal dramatic terms. Certainly it seems alien to American drama. But it does seem to be a distinctively Canadian choice, and I think it’s significant that this particular idea of Ellison’s was jettisoned. Canadians try to get along, even if we’re not happy with the situation, rather than hunt or flee each other.

But we can probably assume that Dullea, Ward and others were familiar with ‘Going Down the Road.’ So, perhaps they were influenced by it, even if only on a subconscious level. Canadian film and literature is not replete with hunters and the hunted. Our mythology lacks gunslingers and sheriffs, lone wolfs, but rather seems filled with people who cling together as they struggle through the wilderness.

Another source of the Canadian-ness of the series was its limitations. Down in LA in 1967, Captain Kirk got into rousing fist fights, crew men died, beautiful women flounced around half naked and someone got laid, guaranteed, every episode. In contrast, The Starlost, five years later in Toronto was much tamer.

Sex? In the episodes of the movie compilations, there was only one genuine babe, the secretary in ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester,’ and she didn’t actually do anything. There was no romantic chemistry at all Keir Dullea’s Devon and Gay Rowan’s Rachel. If anything, there was a tiny hint of sexual or romantic subtext between Devon and Robin Ward’s Garth, and the occasional star crossed romance that was suggested, as in Pisces or the Alien Oro was so tepid as to make no impact at all.

Violence? That did a little better. There were brief badly staged fistfights in the ‘Implant People,’ in ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester’ a gun is actually fired. Threats were made in both Oro episodes, but compared to American or even British programming of the time, The Starlost was remarkably placid.

Why? I think part of this was that the Starlost was coming from a different technical culture than Star Trek. Look at it this way. Where did American television get its ideas? Where did they get their writers, their directors, the cinematographers, stuntmen, fight choreographers, cameramen, technical people left and right?

From the movies. This is hardly rocket science. American television emerged mostly in LA the same place that American film had grown up. When American television was taking root, producing its own dramas and comedies, it was drawing on the collective technical skill, people, visual and aesthetic traditions developed over some forty years of movie making at every level on a massive scale. In many ways, American television simply tried to be American movies on a smaller screen.

For the most part, a Canadian film and Television industry didn’t exist, or barely existed back in 1972 and 1973. I believe back in 1973, the entire feature film production for the entire country consisted of perhaps three feature films. That’s three low budget minor films, compared to something like two hundred or more coming out of the United States.

(One of these Canadian films, The Neptune Factor, was the most expensive and for many years, the highest grossing Canadian film. I saw it when it played at the Drive In. Basically, a bathysphere is lost on the sea bottom, there is a rescue expedition, they encounter ‘monsters’ which are optically enlarged tropical fish molesting tiny props. It really was that sad.)

Of course, the National Film Board was notable for producing documentaries and shorts. On the television side of the coin, there was the CBC, which did some children’s programming, like Romper Room, a game show or two, like Front Page Challenge, news programs, documentaries, broadcast a lot of hockey, and occasionally committed to Wayne and Schuster Comedy Specials, the occasional dramatic one off, and a couple of half hour series like King of Kensington and Beachcombers.

Harlan Ellison writes, and Norman Klenman, confirms that they had no scriptwriters in Canada. There were good Canadian script people, Klenman among them. They were all down in L.A.. Why? Because there wasn’t enough industry in Canada to support them.

Well, think about that for a second. If there wasn’t enough of a film/television industry, if there wasn’t a solid base of sitcoms and dramas to support writers, then probably there wasn’t enough going on to support directors, cinematographers, effects people, the whole infrastructure of skilled technical people that you need to pull off a polished action/adventure show like Star Trek or even a generic program like Mannix.

There were skilled people in Canada, of course, but lets face it. Being a cameraman on a game show like Front Page Challenge was a very different thing than being a cameraman on The Starlost.

So, if the Starlost wasn’t drawing on the same kinds of technical and talent bedrock as Star Trek, where were its traditions coming from, if anywhere?

Well, if American television grew out of American film, and the decades upon decades of accumulated skill and experience that went into film, then arguably, Canadian and British television sprang from a different source: The stage.

If Canada didn’t have a well established film tradition, it did have a very well established stage tradition. Starting, like the Americans, with the Vaudeville circuit, Canada maintained a small but lively theatrical community. Every major city had a theatre, and even small towns had performing halls for live entertainment, there was a major Shakespearean festival at Stratford.

It was a theatrical tradition which was hardly large by any means, I suspect most Canadians were too busy watching hockey to even notice it. But it was there, an integral part of the Country’s culture, and integrated enough into Canadian society that it would perform the works of Canadian writers.

The bottom line, is that if you were in Canada and hiring actors, a lot of what you would get was going to be theatrically, rather than cinema, trained. Same thing with local directors, writers, lighting people, set designers, prop-masters, make up artists, etc.

This actually shows in the stuff that was appearing on television. Most of the CBC’s dramatic specials were adaptations of stage plays, often shot as if they were on stage, with minimal sets, basic lighting, few changes and so forth. Lets face it, there wasn’t a lot of money in the CBC budget for drama in the first place and not a lot of experience with the format, so adopting a theatrical style with its built in limitations was both cheaper and easier than a more cinematic style.

“The show’s distinct quality was due not simply to a starved budget or inferior production techniques, but to a creative sensibility that was perhaps not readily understandable by run-of-the-mill (American) science fiction fans. The theatrical orientation of the writing could be seen in the way the dramatic crisis of each episode was structured — not as an “action scene”, but as a dialogue, or perhaps monologue, setting out a conflict of ideas. “The Return of Oro” is an obvious example, but I am thinking also of the interesting speeches in “Gallery of Fear”, “Circuit of Death” and “Mr. Smith of Manchester”. The use of theatrically trained supporting cast was often quite evident, with bit-parts being executed with surprising panache (i.e. the spokesman for the fearful citizens in “And Only Man is Vile”, and the council leader in “The Implant People”). Contrary to an oft-repeated criticism, the acting was generally of a high calibre; the difficulty, rather, was that the minimal number of cast members in any given episode put a lot of pressure on the regulars and guest stars, making it harder for them to realize the story’s dramatic potential,” Boris Bohuslawsky wrote to me in private correspondence. I think he was on the mark enough to reproduce his comments here.

American cinematographers and stuntmen had forty years of westerns under their belts in creating exciting and convincing fistfights. The Canadian production crew, being basically stage and non-dramatic television, had none of that. As a result, we’ve got an extremely badly staged fight in ‘The Implant People.’ Well, if they simply weren’t good at it, perhaps it was best that they stayed away from that sort of thing.

The British had a more sophisticated film industry, with numerous films made as far back as the thirties, forties and fifties. But, the British film industry was born facing an extremely well established and entrenched theatrical culture. Throughout its film history, for most British actors, film was just something you did, while real ‘acting’ took place on the stage. British film, for much of its history, was shaped by the conventions and ideas of theatrical tradition. British television, when it came along, took its cues from the stage, rather than film.

Interestingly, however, Hollywood never really had a stage tradition of its own. It was a factory town, and the factory made movies. Stage actors or technical people tended to slip some influence in, but they were coming from New York, or even London. So they never had the kind of influence in far off California that they had in England. Hollywood movies evolved on their own, taking various influences, but genuinely becoming their own creatures.

The result, however, is that Canadian and British television drama, like the Starlost, tended to be more formal than its looser and more natural American counterparts. They tended to be talkier, more thoughtful and slow paced, with more emphasis on acting and characters, more on ideas, less on action. Some of the most gripping scenes are simply framed as debates. Characters tended to be more interesting, more unique and less stereotyped. On the other hand, they tended to be less active. The staging tended to be simpler and economical, with minimal special effects or action scenes. The acting tended to be more deliberate and less spontaneous. Even the rhythms was different.

Does this make British or Canadian television naturally inferior to its American counterpart? Not necessarily. British television has produced some spectacular offerings, through which its stage origins show through clearly: Masterpiece Theatre, I Claudius and even Fawlty Towers are justly regarded as classics. On the sci fi side, the Quatermass serials, Doctor Who and Blake’s 7 are clearly stage born, and just as clearly enduring genre works.

Interestingly, the advertising and video boxes for the Starlost compilation movies goes out of its way to mention Doctor Who as well as Star Trek, clearly recognizing a similarity in style and format.

But, if the Canadian style tended to resemble the British in being more theatrical rather than cinematic, it was clearly genuinely less sophisticated. At the time that the Canadians were trying to syndicate The Starlost to American markets, the British were doing the same thing much more successfully with Space: 1999, by far the more polished and cinematic of the two, as much a child of cinema as of the stage.

Unfortunately for The Starlost, it was being marketed primarily to an American audience that had grown up and was used to the cinematic Hollywood style. Its more sedate and cerebral theatrical origins and style was pretty much lost on an audience acclimated to the thrills and chills of Star Trek.

Another factor we have to consider is that the standards existing at the time for Canadian television were much more restrictive.

Ontario, the Canadian Province where the Starlost was shot, was so conservative that it became one of the last jurisdictions to maintain a film censor board. Ontario was, and still is, famous for its prudish and pedantic censors. The governing bodies of the largest and wealthiest province and City in Canada liked to compare themselves to places like New York, go there and you’ll hear a lot of talk about being ‘world class’ but the truth is that historically and to the Toronto is more of an Minneapolis or a Des Moines class city as far as community standards and culture goes. There is a deeply conservative, perhaps even timid, thread within Toronto’s cultural mainstream.

This is a place that banned internationally acclaimed films like ‘The Tin Drum’ well into the 1980’s, and in the 1990’s was seizing paintings from art galleries and putting them on trial in the Eli Langer case. So right from the starting gate, the community standards were profoundly prudish with regard to sex, and only a little less so when it came to violence.

Television content, and standards of acceptability were defined by the CRTC (Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission, the Canadian equivalent of the FTC), and were guided or further defined by the CBC.

CTV at the time was a fledgling network, it was a chain of private television stations, which had just begun to invest resources into its programming. This was literally its first attempt at a dramatic series. In a climate as conservative as Canada’s, it probably had no intention of rocking the boat, of going out and taking risks. This was a major effort and a lot was riding on it.

So, we weren’t going to see a lot of adult sexual content or situations, or if that was present, it was going to be played in a very subdued fashion. Violence was going to be used sparingly. Part of this, of course, may have been a hidden sensibility that sci fi was actually children’s programming. In a sense, perhaps they were taking a leaf from Doctor Who, rather than Star Trek.

The creators of Starlost were trying to create something for the American market. Their goal was a kind of simulated ‘Americana.’ Well, they clearly failed in doing that.

Later productions, like Night Heat or Street Legal would come much closer, and be much more successful in creating a product indistinguishable from its American peers. By the 1990’s, sci fi programs like Stargate, Andromeda, Earth: Final Conflict and X-Files. conceived in the US and owned by US companies, but shot in Canada, would look and feel absolutely American. Is this a better or worse thing?

The Starlost was a cruder production, less American in look and feel. Does this suggest it was more naturally or inherently Canadian? I don’t know that amateurishness, if we want to be cruel, is distinctly Canadian. It’s definitely true that there wasn’t a lot of money or resources for production design, by modern standards its bare. Quite often the music, the lighting, the cinematography seem… basic.

But was it all simple crudity, or was it the traces, however young and poorly developed, of a distinctive style and sensibility. I think at least some of it, beyond the threadbare qualities, was a different style, a different set of choices, different but legitimate.

Which gives one pause to think. Obviously, if the Producers of Starlost could have emulated the American model perfectly, they would have. There’s no question about that. They were trying to create a product for the American market, not create an artifact of Canadian culture. But, culture, inherently, is an expression of who you are.

The thing with Canada, is that we live right next door to a neighbor who is ten times our size. We speak the same language, we share history, values, clothes fashions, we share our economy, we work for them, some of them work for us, we have the same technology, books, movies, television. In a sense, Canadians and Americans are literally identical.

But we aren’t identical. We’re a separate country, a separate history. We know it, and the Americans know it too, they know we’re not quite American, we don’t have the same rights and privileges, we don’t have the same influence.

But if we are a separate nation… Who are we? Who are Canadians? What does it mean to be Canadian? What do we stand for? What are our values? Our goals?

And how do we find this, how do we establish this, when our neighbors to the south are so huge, their presence to overwhelming. When American companies own half our businesses, when American television is 90% of the television we watch, when American movies are 99% of our screens? How do we find our nation, when we are a satellite orbiting the American planet, ten times our size.

Beginning in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Canadians began to ask these questions, began to struggle with these issues. We’re not Americans, so who are we?

Sometimes that was seen as just ‘we’re not Americans!’ That can be seen as Anti-Americanism, this defiance, this insistence on taking an identity that we feel threatened and assaulted by America. It’s not that Americans are actively the enemy, they’re not stealing or suppressing our culture. But they’re so large and loud, that trying to establish who we are often involves the struggle of saying ‘we aren’t you!’

Which leads to people befuddling a puzzled Ben Bova with talk about ‘fleas in bed with elephants’ I’m sure he must have thought it was insane, all these people, utterly indistinguishable to him from the folks back home, with these weird chips on their shoulders. It would be an utterly alien, out of the blue thing. These issues weren’t anywhere on the radar in the US, then he comes up here, and he’s dealing with these people who are just like Americans… except every now and then they turn into angry Martians.

But it’s a real thing. The truth is that we’re like Americans, but we aren’t Americans. That’s one of the things that defines us. We see Americans very clearly, perhaps more clearly than they see themselves. We find an identity in being smaller, in being next to a giant, in our own concerns and priorities. I think nowadays, we’ve got it mostly sorted out, for better or worse.

At least, we’re not wandering up to each other in the streets of Toronto or Vancouver having discussions about what it means to be Canadian.

But back in the 1960’s and 70’s, we were having those discussions, we were having serious discussions everywhere. Everyone was talking about it. We were redoing our flag, we were writing new songs, the government was launching all these programs and initiatives. It was a big thing.

And, going by Ben Bova, it was also a big thing on the sets of Starlost. It makes me want to find and apologize to him, his comment about weasels being the national animal of Canada notwithstanding. He just had no idea what he was walking into. But the point is, it was there.

There is a thread of Canadian sensibility, even Canadian Nationalism, that runs through the series. Many of the episodes and stories seemed to address specifically Canadian issues. Arguably, the production and design style, beyond its obvious poverty represents something decidedly non-American. Even the series premise seems oddly Canadian in its perspective and outlook.

The basic concepts of Starlost seem oddly Canadian. Let’s face it:

A group of autonomous communities loosely tied together, oblivious or indifferent if not downright hostile to each other, drifting along without direction or leadership, heading slowly for an impending doom that everyone sees, but no one seems determined to avoid.

Well, if that’s not a blatant metaphor for the Canadian experience, for the actual state of Canada, especially Canada in the late sixties and early seventies under Pearson and Trudeau, then I don’t know what is. We were a pack of squabbling provinces, each of us autonomous, loosely tied, just drifting along… Did we have a national identity, national policies, a national economy? And doom, well, we weren’t sure if our country had a future, maybe Quebec would be independent, maybe the rest of the provinces would fall into the United States.

You couldn’t get more Canadian if you stapled Margaret Attwood to W.O.Mitchell and launched them into orbit (Wishful thinking there).

EXPRESSIONS OF CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND SENSIBILITIES IN THE STORIES

For whatever reasons, Canada is a distinctly ‘greener’ and ‘gentler’ place than the United States. The United States has defined itself and its mythology is expressed as wide open spaces and frontiers to be explored and tamed. As we’ve already noted, in Star Trek, space is the final frontier, and it’s treated like that, with prospectors, settlers, explorers, backward natives, swarthy hostiles and even barroom brawls in frontier saloons.

Canada’s self image and concerns seems to express itself in more timid terms. Our environment, like space itself, is conceived as immeasurably vast, implacable, almost overwhelming, it is something that defies conquest. Rather, existence is hard won, the result of conservation and hard work, delicate networks of contact and communication, farms, homesteads, even towns and cities literally built as shelters against an empty nature which ruled once and may rule again, much as the vast Ark is actually a delicate construct in the empty vastnesses of space.

Boris Bohuslawsky, who I corresponded with, pointed out, “the sense of vast, desolate space which was so effectively communicated by the visuals of unending deserted tubes, and of the exterior of the ark itself — the camera often getting beneath the domes and in between the tubes to capture the model’s extraordinary detail. Ultimately, what was unsettling about the show was the sense of loneliness it created. Whether or not this was deliberate is impossible to say, but this characteristic would certainly be of a piece with other expressions of Canadian culture and identity.”

The oddly schizophrenic view of Canadians, of nature as being both vast and implacable and delicate and in need of conservation finds an odd synthesis in The Starlost. Literally, the Ark is vast, its literally worlds, but its also finite, where they live, its parts in delicate balance, showing wear and tear, but in the end, its all they have.

Or maybe its not schizophrenic, maybe the Canadian sense of nature is that it is vast and implacable, and what is delicate and needs conservation, is simply our own place in it, requiring cooperation and mutual support rather than conquest and personal success.

These ideas show up again and again in the show.

For example, an oddly Canadian aspect of Starlost might be described as ‘fear of America.’ Like it or not, the United States will always be a dominating force in Canadian life and thought. This country was founded, more than any other reason, to survive the Americans. To keep from simply being swallowed up, bit by bit. The United States has ten times our population, and for geographical reasons, even that effect is magnified, the Canadian population is stretched out on a ribbon along the US border, a few hundred miles wide and thousands of miles long. They influence every aspect of our existence.

At least a few of Starlost episodes deal explicitly with this theme. ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester’ represents a first portrait of American society. It’s a society obsessed with production, with guns, it’s a militaristic society with literally no one to fight. Manchester is all alone in the dome. It’s worried about the threats of other domes, to the point where it’s a totally militarized, totally industrial society. It’s a society wrapped up in paranoia, planning a defensive conquest of the Ark, and literally drowning in its own pollution.

Is this really the United States? Consider the time. 1973. The United States was just up to its elbows in the Vietnam War (a war that Canadian governments were pressured to join). The illegal bombing of Cambodia and Laos is an open secret. The CIA is exposed overthrowing governments and plotting assassinations in South America and Africa. The FBI is wiretapping its citizens. The White House is keeping a list of enemies and Richard Nixon is slowly being exposed as the psychopathic liar he was.

From north of the border we were looking at a society whose cities were visibly decaying into sprawling slums of poverty and misery while the well to do fled to suburbs. It was a society opening fire on its own University students. It was a relentlessly aggressive militaristic society, obsessed with enemies who were at least half imaginary (communists under the bed, anyone?), and consumed with the idea of growth at all costs.

Smith’s Manchester was a dead on outsiders portrait of Nixon’s America and all its jingoism, militarism and paranoia. Manchester is obsessed with growth, obsessed with production, Smith boasts of breaking records – even while the Dome is becoming uninhabitable from its own smog and pollution. Smith’s optimism and drive speak to Manifest Destiny, they’re ready to expand, to take over, and they believe that they’re entitled to do it. More clues come from its presentation. If Manchester had been intended as a parable about the Russians, for instance, it would have been easy enough to make it clear. The characters don’t have funny foreign sounding names, as Roloff does in ‘The Implant People’ but good old North American names like Smith and Trent. They don’t have foreign accents.

The lead, Ed Ames, who played Mr. Smith, was best known previously as an actor in westerns. He has no accent, he speaks with a down home American twang. There’s no effort at all to come across as foreign or alien. Rather, the horror of Manchester is in its down home quality. And of course, the fear of Manchester getting out, is not simply that it would take over, but also that its pollution might contaminate the entire Ark, which distinctly encapsulates Canadian fears. Manchester and its runaway industrialization, its production and pollution, taking over the Ark reflects a Canadian nervousness, not just of American pollution, but Americans taking over the whole country.

In hindsight, ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester’ seems such a blatant and subversive piece of anti-American propaganda that one wonders how it got made at all, much less presented to an American marketplace. Certainly if the Americans had perceived that they were being skewered, many of them probably wouldn’t have liked it at all.

Another key episode which seems drenched in Canadian Nationalism is, ‘The Alien Oro.’ Devon, Rachel and Garth discover an alien, Oro from Exar (XR) played by Walter Koenig.

It’s telegraphed. Oro is spanish for ‘Gold.’ And Oro is about the money, he continuously refers to the Ark in terms of wealth or resources. His society’s name, Exar is clearly reminiscent of the US. Oro’s world is pronounced Exar, the phonetic rendering of XR, I’ve seen it spelled as Xar or Ixar, but in the absence of a script, I don’t believe there is a definitive spelling. But XR, a kind of two letter name from the back of the alphabet, just like the US. There’s a very strong hint that Oro’s world, and his attitude is an analogue for America.

Oro’s ship has crashed on the Ark, and he’s been playing Robinson Crusoe. In particular, he’s been cannibalizing parts of the Ark to fix his ship. Normally, this is a pretty standard adventure scenario. But Devon and his friends are appalled. For Oro, the Ark is just resources, he’s just here to take what he needs and leave. But they’re living there, they have to live there, they’re upset with him plundering. How does anyone know that he won’t take something vital to life support, or steering? Eventually, Oro is allowed to leave, and he promises to try and send help back.

But there’s a deep disquiet in the episode that seemed to reflect disquiet and tension about American ownership and investment in Canadian resources. And this disquiet joined up quite neatly with the Canadian environmental movement. Environmental movements were universal of course, you saw them in the US, and in Europe – people everywhere were coming to grips with pollution. But in Canada, because of the effects and proximity to the United States, environmentalism merged neatly with nationalism.

Our raw materials are cut down, or dug up, and shipped south. our land is bought out. How do we feel about that? Back in the early 70’s, for instance, the Province of Prince Edward Island was so concerned about foreigners (Americans) buying up the cottage land, they actually passed laws restricting it.

But the issue was larger than that, there was the sense that America looked to Canada as a place of resources and raw materials. Canadians were concerned about being plundered, about forests being cut, mines despoiling the land, rivers poisoned and factories and jobs being shipped south. It was all very well for Americans to look north and see vast resources, but Canadians had to live here, and we weren’t thrilled with our country carted away, or the contamination left behind.

So what we see in Mr. Smith of Manchester is that fear and disquiet over pollution escaping over the border, poisoning our landscapes. And in The Alien Oro, there’s the mercenary plundering of the Ark’s resources, without thought to consequence.

Canadian nationalism looms large in ‘The Return of Oro.’ Here, instead of going to the US as in Manchester, the US, in the form of Oro of XR comes to our heroes. This was the only sequel episode. I think we can assume that there’s something very important about the character of Oro and his society, someone is trying to say something. It’s got Walter Koenig from Star Trek as Oro, of course. But Koenig wasn’t a particularly big name, compared to some of the other guest stars. Rather, I’d say that having two Oro episodes suggests that there’s some key issues and concerns being expressed.

Oro shows up again, but this time he’s not a castaway. When he left, he’d suggested that he may bring help. Instead, he comes back with an offer. The Ark is an incalculable bounty of resources, XR wants to own it. So his offer is: Hand it over. If Devon and the inhabitants are prepared to surrender it, then the XR will tow it into orbit and it will become their satellite. Say no, and take the chance of falling into a sun. This sets up the terms of a debate, judged by the ships artificial intelligences, as to whether to sacrifice their independence and become a satellite, or continue their own way and risk destruction.

He comes as a saviour, he smiles, he’s friendly, he makes a pitch even showing home movies of his planet and his good intentions. But in the end, he basically wants the wealth of the Ark. The climax of the episode is a debate to the death where Oro offers survival and security as a satellite and colony of XR and Devon speaks on behalf of freedom and charting their own course, even if the risk is disaster.

This was actually a very Canadian debate, especially in the early seventies when Canadian economic nationalism, advocated by people like Walter Gordon and Mel Hurtig, was at its height. Canada faced a kind of crossroads, and it was very much like the question in ‘The Return of Oro.’ Indeed, the language used in Return of Oro, the terms of the debate is identical to what was playing out in Canada on television, in coffeeshops and at universities.

Canadians were basically looking at their future and trying to decide if they had one. Was it possible to have an independent Canada, a nation that charted its own course, sought its own destiny? Could we control our own economy, have our own businesses and policies? Could we survive that way? Or should we embrace the security, the easier path, of just being an American colony? Would Canada’s resources be owned by Canadians or by Americans?

In the end, Devon wins the debate, not necessarily because his argument is more logical, but because it represents the values of the ship and its people. Which is a particularly, peculiarly Canadian reasoning. We weren’t sure that Canada made sense from a strictly logical point of view, but we still believed in our country anyway.

It was a uniquely Canadian debate. Let’s face it, the Americans weren’t sitting around asking themselves if they wanted Canada for a satellite or not. The Americans had never ever doubted that they were the masters of their own destiny. They were no one’s satellite, in no one’s orbit, they acknowledged no gravity but their own.

In short, this sort of debate was absolutely foreign to them. Nothing quite like it ever comes up in Star Trek, for instance. Captain Kirk might occasionally encounter gods or superior beings, but they were almost invariably frauds or crippled with weaknesses, or at the very worst, they were the real thing but they minded their own damned business. Even the Organians who prevented a war had no further influence on the hearts and minds of the Federation. Kirk never needed to worry about the Federation being drawn into Organia’s orbit and becoming a satellite society.

Internationally, many countries, including France, Britain and Australia found themselves complaining of the weight of American power, the omnipresence of Coca Cola and Mickey Mouse.

But these complaints were a distant echo of the situation in Canada where we lived literally cheek to jowl with the American behemoth. No major nation in the industrialized world quite confronted the sort of colonial issue with the United States that we were looking at in quite the same way or quite as profoundly as we did.

This was one of the most popular and crucial debates of that time period. From it arose a real movement to try and preserve or take back Canadian society and economy. On the business side of things, there were a number of moves, like creating PetroCanada as a national energy company and restricting or controlling foreign investment and takeovers through the Foreign Investment Review Agency. On the social side, there was a concerted effort to lay foundations for a viable Canadian film and television industry. The national debate would give rise to the tax shelter film boom, which would literally create a Canadian film industry overnight. It also spurred cultural funding agencies, everything from the Canada Council to Telefilm.

In short, its absolutely impossible that the people making Starlost in Canada, those writing it, acting in it, producing it, could be unaware of this national debate. As Ben Bova notes, they were definitely talking about it. Hell, in a very real sense, these people and the nascent film and television industry they represented, even had a personal stake in it. They were inevitably in the center of the cultural storm. It’s not a coincidence.

The language of the debate, inspired by a space program that was still putting people on the moon, was laced with space opera. Canadians talked in terms of being an American ‘satellite,’ of Canada being in the American ‘orbit,’ of the ‘gravity’ or ‘gravitational force’ of the American society and economy. It’s a small step rather than a giant leap to transpose the whole thing into a sci fi palette.

‘The Return of Oro’ then, wasn’t just about XR taking the Ark for its own purposes, but it was really about the debate over the heart and soul of the Canadian nation. The debate as to whether to become a satellite or colony, to be drawn into the Exar orbit and lose their identity or try to be masters of their own destiny even if that does not seem a viable clearly drawn from Canadian nationalist debates. There is, frankly, no comparable parallel in American culture, or even in British or European cultures, this must be seen as unique. One of the final episodes of Starlost then, is one about identity and remarkably, this debate over identity seems framed in uniquely Canadian terms.

Themes of conservation shows up several times. If space was the final frontier in Star Trek, the Ark in Starlost is a place of finite wealth. In ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester,’ unrestrained industrialization has made the environment all but unliveable.

There’s something very Canadian there. Both Canada and the US are huge countries with vast spaces. But the attitude of the two countries is very different. Americans saw a massive open frontier to explore, to conquer, to settle. Canada, being further north, its climate much more implacable, had a different view of its open spaces. For Canada, the open spaces were implacable and indifferent, you didn’t conquer them, you survived or endured them. You built enclaves or shelters, carved niches to survive in that endless expanse. For Canadians, it was about survival, not conquest. It was about fragility and delicate balance. If you messed around, you might not survive the winter.

In ‘The Implant People,’ a similar degradation of the environment, an expansion of poverty and misery, is hinted at. In ‘The Alien Oro,’ Devon reacts with horror to Oro’s dismantling of pieces of the Ark to repair his ship. To Oro the Ark is resources, to Devon, it’s a finite home.

This is a theme that returns again in ‘The Return of Oro’ and is expanded upon, where Oro continually refers to the Ark as a resource to be acquired for his people. The images that Oro shows of his world in that episode are of pristine wilderness, itself an environmental message, which contains its own subtext. These images turn out to be archive footage of earth, a lost wilderness, a historical record rather than a live place.

It’s true that themes like pollution or the Orwellian state were not unique to Canada. They must be seen as being common to any industrialized society. Whether you are in England or Germany, the United States or Canada, sooner or later you’re going to come up against these issues. Each state or each population has concerns over pollution and the degradation of its environment. Each people have potential concerns over state oversight and infringement of liberty.

But each nation also expresses its concerns differently. Even in the case of pollution, for instance, the issues differ with each nations particular physical concerns. Canadians focused on acid rain, we focused on foreign contamination seeping over our borders, we worried about our lands and resources being taken up or polluted by invaders who had no stake in our country. Japanese tended to focus on water quality because of their dependence on the fishery. Smog prone London and L.A. were concerned about air. Nations where farmland and industrial lands were cheek to cheek worried about contamination of foodstuffs.

Even the degree of emphasis changed from culture to culture and over periods of time. The United States, for instance, has never accorded industrial pollution anywhere near the level of concern that Canada has. Nor for that matter has it ever questioned seriously the limits to growth. In contrast, American anti-state powers paranoia has always reached much deeper into the fabric of their society than ours.

Consider the fear in ‘Mr. Smith of Manchester,’ that the pollution will simply spread across the border and poison or contaminate the whole Ark, as a reflection of the Canadian perspective on pollution like acid rain as being a cross border phenomenon.

Generally, Canadian sensibilities tended to be more focused on environmentalism than Americans. This may be due to the fact that many Canadians live in close proximity to American industrial development, we see pollution first hand sweeping across the border as acid rain, smogs, toxic seepage and polluted waters. It may also be that our environment is comparatively harsher than the Americans, and thus we are more concerned with long term survival, with preserving it than spending it. Alternately, this may be a defensive reaction to the fact that ours is primarily a resource economy, Canada’s wealth is built on the extraction and sale of our finite natural resources, which raises a subliminal concern about what happens to us when its all gone.

A MORE SUBTLE CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE