I was watching Super 8 last night. That’s the J.J. Abrams tribute to the 80’s, and Steven Spielberg movies. It has that same sort of feel of Stranger Things. Likely because they both have the same inspirations, ET, the Goonies, kids adventures and Steven King novels.

One of the cool things about Super 8, is the movie within the movie. The kids are using Super 8 cameras to make their own little epic. The connection is tangential, their Super 8 project means that they’re in the right place at the right time to see the train wreck which marks the alien escape and the main plot.

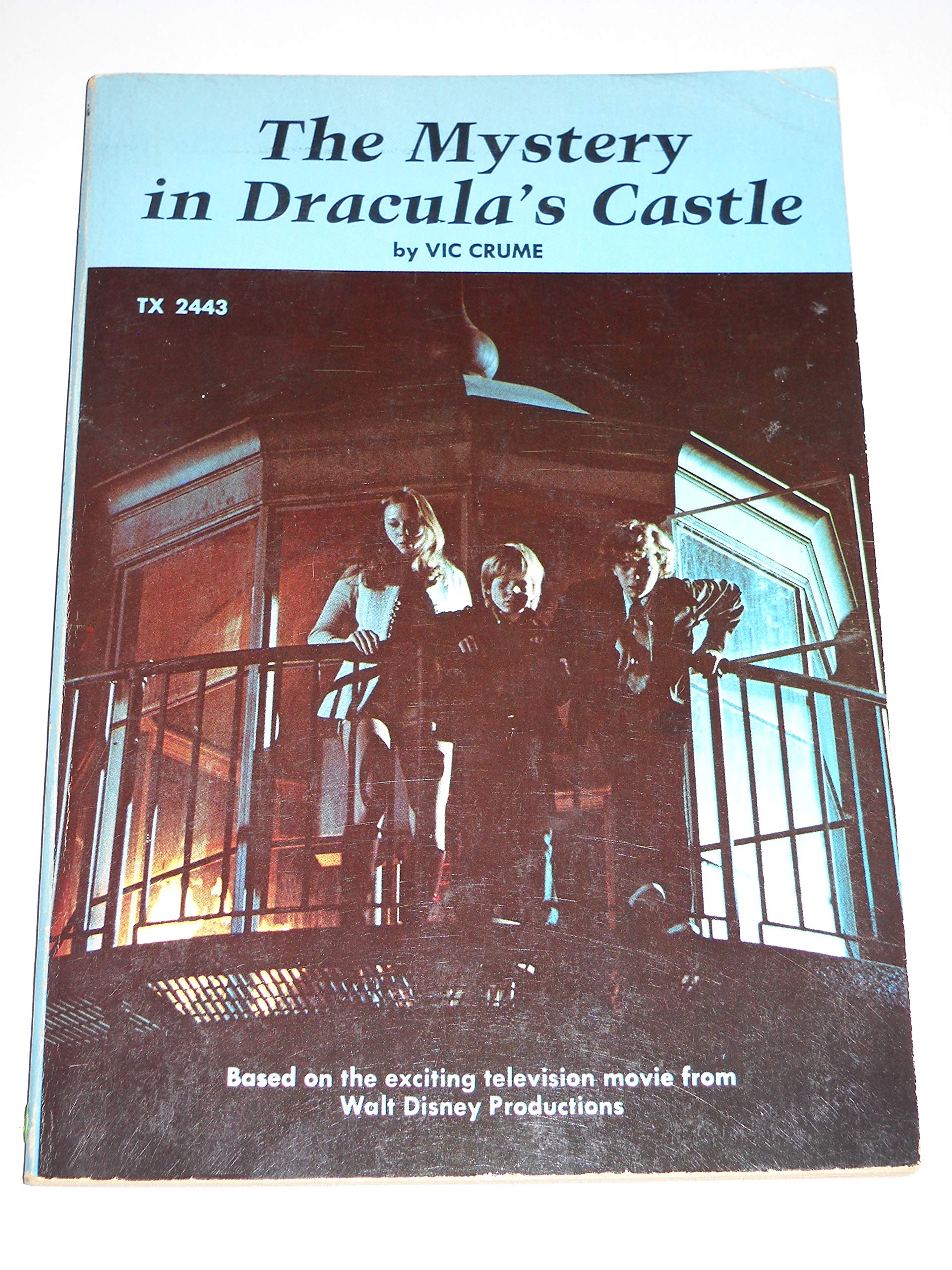

Oddly, that reminded me of a movie I hadn’t seen in a long time. The Mystery in Dracula’s Castle. This is an oldy, it aired way back in 1973, as a two parter, on the Wonderful World of Disney. Later on in the 1980’s, the two parts were stapled together and it floated around on cable channels.

Basically, the story is that a small group of kids get inspired, and decide to make their own version of Dracula on mom’s trusty Super 8. This intersects with the “A” plot which involves a jewelry heist, when the kids decide that the lighthouse the gang is hanging out with their ill gotten jewels turns out to be the perfect location for their Dracula movie.

Honestly the “A” plot is nothing to write home about. It’s straight out of those Hardy Boy mysteries I used to read as a kid, where the mystery isn’t terribly mysterious and the villains aren’t especially villainous.

Despite that, there’s a charming naivete to the thing, the lead villain, played by Clu Gallagher comes across as a charming friendly presence, almost more an uncle or father figure than a bad guy. For some reason, I remember him as Dick Miller. The bad guys schemes aren’t all that menacing, and often they seem almost affectionate – despite doing a bad thing, they’re not bad guys. The chemistry and acting among the kids and their situations in life works, and while the film is viewed through their eyes, you get a sense that the world of the adults around them is a bit more complicated than they appreciate. It’s a decent kids film.

From the vantage point of decades, what interests me most is that this is a movie about a fan film, although no one was using that term at the time.

In 1965, the super 8 camera format came to the public. Now before this, most film came as 35 mm, and 16 mm. Once in a while there were off formats, but those were the main ones.

They weren’t user friendly. The cameras were expensive, delicate and cumbersome, you had to load and thread the film by hand and in the dark, otherwise the whole thing would be exposed. You’d have to go to a professional lab to get it processed. It was just a bag hammers.

The Super 8 format when it came out in 1965 changed all that. Basically, it was an easy sell – Super 8 movie cameras were small, hand held and durable. They could handle the bumps and scrapes of everyday life. And best of all, the film came in cartridges. Pop one in, your movie camera was ready to go. Each cartridge was about two and a half minutes. When it was done, you popped it out, and that was it. Loading and unloading was quick and easy. The film cartridges could be processed at the local drugstore or photo shop.

Playing it was a little more complicated and a little more expensive, but not unmanageably so. What you needed was a Super 8 film projector and a screen. It was a little bulky, but not much more than the old style portable typewriters, the projectors came in a carrying case. You needed a screen, and a darkened room. But it was manageable, a lot of families had them, as did schools, community centres, senior centres, recreation clubs.

Suddenly, every family could have its own movie camera to commemorate vacations, birthday parties, family gatherings, weddings or whatever. The era of home movies had begun.

My grandparents had a Super 8 camera, I remember growing up, seeing films of our birthday parties and pay. I remember a film of my sister, when she was five years old in her dress, carrying her birthday cake all over the room, including in and out from under tables, very purposefully, right up until it fell. There were short films of my uncle, of us kids at the cottage. There were a lot of memories in those films.

I remember, growing up, we grandchildren, my siblings and my cousins, would have movie nights. We’d go over to our grandparents, grandmother would make popcorn, grandfather get the projector set up in the basement. We’d watch old cartoons, bits of westerns, newsreel footage of the Mercury and Gemini missions.

That was a thing – once these projectors were proliferating, there was actually an industry that sprang up to sell commercial Super 8 movies. There were training and industrial films of course. But there was quickly a consumer market for shorts of all kinds.

Even real theatrical movies would be edited down to ten or twenty minutes and sold as Super 8. You could watch the ten minute version of the Seventh Voyage of Sinbad, or Planet of the Apes. Hell, you could own it.

That seems vaguely ridiculous now, like some sort of parody sketch. But it was deadly earnest. You have to remember that in those days, the 1960’s and 1970’s, a decent sized town might have only one or two movie theatres, and at best two or three television stations. The era of cable and dozens of stations, the worlds of VHS and DVD stores, the universe of infinite streaming online content just didn’t exist.

Nowadays, if you want to watch the entirety of the Planet of the Apes franchise, or all of Star Trek, well, it’s basically at your fingertips.

Then, not so much. So these edited down, mini-movies, were pretty astounding stuff, especially for kids who had an insatiable hunger for them. If you look to magazines and comics of the era, you can find plenty of advertisements for these little movies.

There was of course the pornographic side. Super 8 cameras made it incredibly easy to shoot pornography. The trick was to get the film developed. Someone had to know someone with a lab.

My uncle collected Super 8 porn films. Some evenings he and his friends would get together at my parents motel, they’d draw the curtains on the lobby, put up a bedsheet on one wall, and show them. I never saw them myself, never knew about it at the time, though I occasionally found the bedsheet up. I heard about it much later. I find myself wondering about those film, who made them, where they came from, what those grainy, over saturated flickering images would have looked like.

Of course, it wasn’t just vacation movies, birthday parties and porn. Super 8 made film making accessible to… Everyone. Suddenly, you didn’t need a film studio. You could just… do it.

People got right into that. Suddenly, they were selling accessories. There were tripods, so you could have the camera fixed and stable for smooth shots. Then editing equipment. Around 1973, Super 8 added sound. Then microphones. A frame by frame function was added so you could do stop motion, and a rewind, so you could do double exposures and special effects. Lights were available. Within a few years, you could literally buy all the equipment you needed for an entire Super 8 film studio. Magazines were published for Super 8 enthusiasts, full of handy tips on everything from scriptwriting, to editing, to model-making. There were even festivals devoted to Super 8.

The result was this really vibrant diverse subculture of amateur film makers at literally all levels and all walks of life, from pornographers and nudists, to enthusiastic kids making their own monster movies. It’s all gone now, and so mostly, what we’re left are just glimpses – references in The Mystery in Dracula’s Castle, or Abram’s Super 8, advertisements in old magazines, which leave us with hints that it ever existed at all.

I find that fascinating. An entire medium of art, a body of work, it all just came and went, and we barely know it ever existed.

People like Spielberg, Lucas, Dante, Jackson even Abrams, grew up as teenagers in the Super 8 era, making home made epics, learning the craft. A friend of mine, Patrick Lowe, made a whole series of Super 8 animations.

But while it existed, we have the beginnings of fan films. This was when kids and adults who were fans started making their own versions of Dracula or Frankenstein, Star Trek and James Bond.

Fandom didn’t really exist back then, in the 1960’s and early 1970’s, not the way it does now. The Science Fiction fan movement started as a literary phenomenon as early as the 1930’s, with the rise of the pulp magazines and radio serials. The first conventions were held around then, and mostly focussed on the literary side, on readers and writers.

Media fandom didn’t get off the ground until Star Trek, back in the late 1960’s. It didn’t coalesce until Bjo Trimble’s letter writing campaign to save Star Trek that resulted in renewal for a third season. The first Star Trek Convention wasn’t even until 1972. The first Doctor Who convention wasn’t until 1977. It’s not until Star Wars exploded over pop culture and literally rewrote the entire landscape that media fandom truly became dominant.

The upshot is that from the late 1960’s through the 1970’s, fans were emerging as a coherent subculture. They were falling in love with Star Trek, Doctor Who, Planet of the Apes, Star Wars. They were writing to each other, creating fanzines, building props and sewing costumes, forming clubs and eventually starting conventions.

And they making movies. With Super 8, you could actually make your own Dracula or Star Trek movie. You could get your fellow fans to help you make it, they had costumes, they had props, they were enthusiastic. Best of all, you had an audience, people like you to show it to, places to share it.

I think that’s an essential part of fan films, not just the culture or subculture, the impulse to create them, but the subculture that supports them, the audience and the venues for them.

The earliest Star Trek fan film is probably a two minute short, with twelve year olds in T-shirts sitting around pretending a living room is the bridge of the Enterprise.

But it got ambitious quite quickly. Here’s the thing – making a film is a collective effort. You need someone behind the camera, you need someone in front of it, preferably several someones. You need a script. You need props and costumes, and someone to create them. You need locations, and to dress up locations. Or you need sets and someone to build them. After all the work is done, you need an audience to watch it, and a venue or a place for that audience to gather.

Before the emergence of fan culture, your volunteers were largely whoever wasn’t running away, your small group of friends, and your audience were those friends and family around the living room. That’s limiting in a lot of ways.

With the emerging fan culture, you had people lining up to volunteer. More than that, you had people who were already sewing their own costumes, or building their own props, because it was just fun. The idea of making a film was enthralling, it was an excuse to build entire sets.

By 1973, you had Paragon’s Paragon, a Star Trek feature length film by John Cosentino, a carpet layer from Michigan. Not only was it feature length, but Cosentino went all out, he literally built an entire replica of the bridge of the Enterprise. He built himself an optical printer, so that he could replicate the effects. He created stop motion monsters, glass mattes, the whole nine yards. By 1979, English fans had created Ocean in the Sky, a feature length Doctor Who movie, with spaceships, special effects, a Tardis interior, and four full sized Daleks.

Most productions were far less ambitious of course, three minute to fifteen minute reels. But most of them had a venue to play in, at fan clubs and at conventions.

Yes, most of them were awkward and amateurish. But I still think that it was marvelous. It was people doing these things for love. It was an expression of both creativity and community. That wonderful urge to just do something. There is a naive charm, and enthusiasm, that balances the amateurishness. And often, there’s a touch of giftedness, an interesting shot, a location, a performance, some special effect carried off with aplomb to appreciate.

Commercial films, it is true, are immeasurably more polished, and have the advantage of a lot more money, more and better equipment, more resources, more trained people. But by the same token, they’re often cynical and sometimes lazy. And their mistakes and failures are lot less forgivable. I’m much more prepared to forgive fan films, simply because they’re working with so much less and trying so much harder.

Of course, there were limits to the format. Super 8 wasn’t designed for narrative film making. Everything from editing, to sound mixing to simply keeping the colour balances consistent posed massive challenges.

The resulting films weren’t exactly portable. They weren’t easy to copy or share. You generally had only the one finished film, and they were subject to wear and tear. So at best, only a few dozen or a few hundred people would see them.

Eventually, come the 1980’s, they were replaced by home video camcorders – camcorders were a lot more user friendly, they recorded for an hour or more, they were easier to edit, and easier to copy. It was home video that brought the real renaissance in fan films. But that’s another subject.

Some people, artists and enthusiasts, stuck with Super 8 for a while, but mostly, the format and the culture just evaporated away. Most of these early ambitious efforts are lost to us now. Long forgotten, some of them perhaps sitting in attics or storage, most simply tossed

I suppose that’s why I have such affection for The Mystery in Dracula’s Castle, and Abram’s Super 8. For me, it’s not the main stories which are pretty standard. But it’s this glimpse into a bygone world of film making, when a small group of young friends could be inspired by Dracula, and could set out to make their own versions, buoyed by enthusiasm.

There’s a heart there, the sort of heart that we see in Stranger Things perhaps, or the Goonies, that make these films, and this forgotten world compelling.