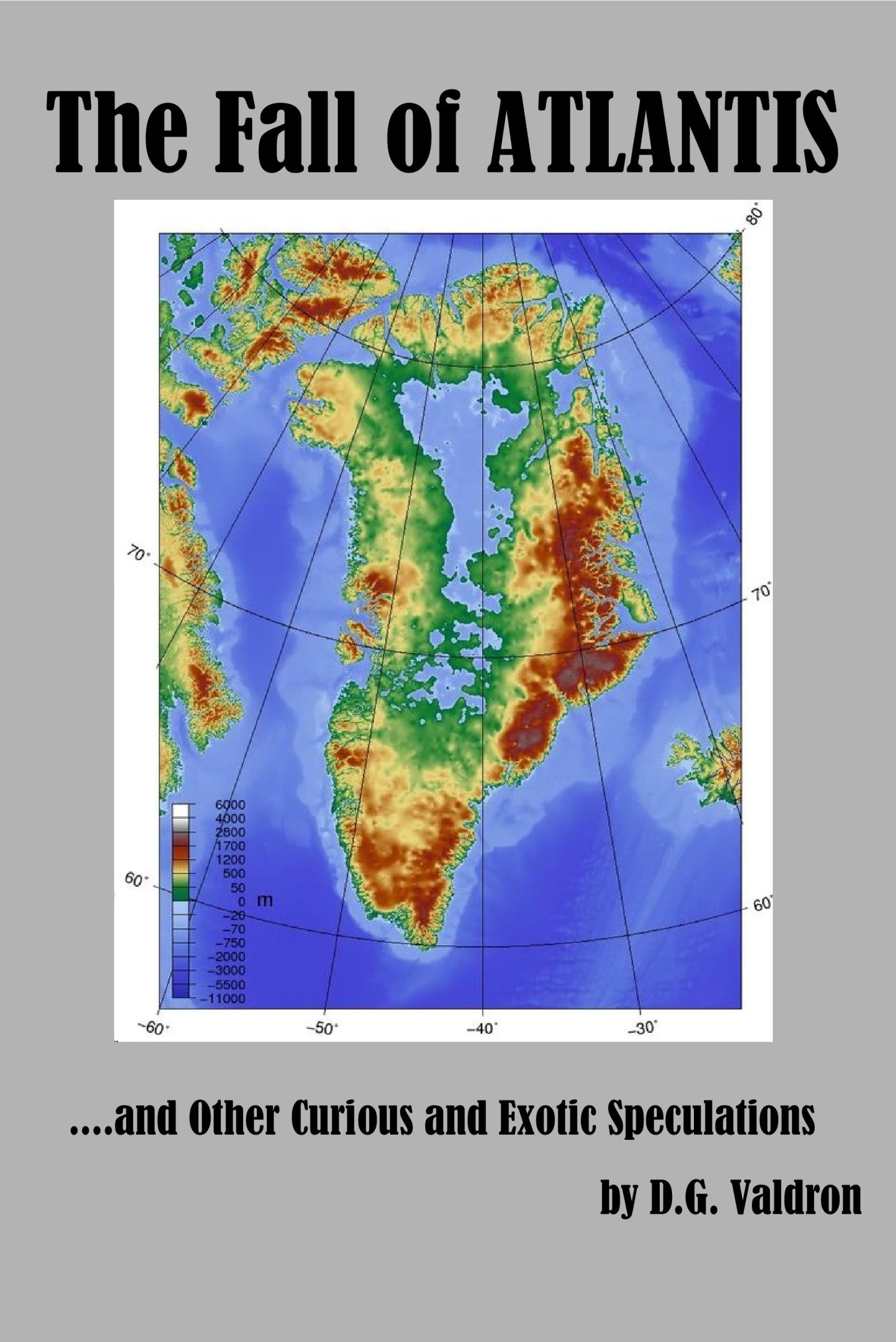

That’s obviously not Atlantis on the book cover. If anything that’s Anti-Atlantis, with it’s central sea in there, surrounded by land and ringed by mountains. That’s an almost complete inversion of Plato’s idea of an Island nation out in the Atlantic.

The picture is Greenland of course. But not the Greenland we know, it’s Greenland without the ice. This is a topographic radar map of Greenland’s elevations. It plays a little trick on us – blue is the colour designated for sea level elevation, so everything on the radar map that’s coloured in blue is at sea level elevation or lower. The green parts are just above sea level. The reddish brown represents mountain country.

It actually gives you a decent idea of what Greenland was like, or would have been like without all that ice. Not a perfect idea, there’s a thing called ‘Isostatic Rebound.’ Basically, most of Greenland is under two miles of ice. That two miles of ice is compressing the bedrock. Take it away, and Greenland will probably lift. But I suspect that mostly, that lift won’t dramatically change what we see I think it’s a fascinating map. It’s filled with possibility, potential. It’s so much better than most homegrown fantasy maps.

That’s the explanation for the Map that isn’t Atlantis, on a book titled Fall of Atlantis.

In a sense, like The Dawn of Cthulhu, this is a book about world building. It’s speculative fiction of the plainest, barest kind, taking ideas like ‘What would Greenland be like without the Ice?’ Or ‘What’s a plausible pathway for the Romans to get to the New World?‘ And just spinning them out and extrapolating. No plot, no characters, but fiction all the same.

Sometimes, perhaps too often, the approach to worldbuilding is like picking items off a chinese menu. One from column A, and two from B, oh and lets try number 42, let’s throw a mountain range down over here. It’s like selecting off a set of options. Sometimes it just doesn’t add up to a whole lot.

Seriously, I’ve seen worldbuilding manuals that are like giant checklists running on forever, nailing down every detail of fantasy or sci fi societies. I don’t know about that kind of meticulous approach. It seems like a lot of work. And it seems… unfun. Almost claustrophobic and lifeless. Whatever you do when you build a world, you want it to feel lively.

Personally, I’m of two minds of worldbuilding.

Firstly, you only need as much of it as the reader sees. Think of your world as a western movie set, where you walk down the streets of an old western town, but if you turn a corner, or walk into a building, it’s all just a facade. The truth is that you don’t need to build every part of the world. You don’t need insane levels of detail. You just need what you actually need.

Secondly, the parts that we see, they’ve got to make sense. They have to feel real. They have to feel authentic, real history, real geography, real biology. It has to feel true. It has to feel like your fantasy or sci fi world still exists when the author looks away, it has to feel that it existed before the characters came on the scene, after they leave, and in the places where they’re not around.

I suppose that sounds like contradictory advice. So be it.

Good world building is tricky. And even when you’re going on the sly, it’s a lot of work.

I find a lot of Fantasy authors cheat a bit – they take an actual period in history, often European history, but sometimes middle eastern, or Asian, they file off the serial numbers, dress it up a little bit, ad some magical elements and voila, fantasy world. Joe Abercrombie, Miles Cameron, Glen Cook, Guy Gavriel Kay and others have all done this. Don’t get me wrong, I love their work. But I’m also enough of an Amateur historian to recognize the actual history they’re filching.

Honest to god, if I have a complaint, it’s with the narrowness of the ‘borrowing.’ We’ve got a massive amount of history to loot for our fantasy, something like six thousand years of it, recorded or reconstructed, and really, we’re only borrowing a few narrow slivers.

But it’s honestly not a bad approach. A lot of fantasy, even science fiction, is derivative. There are very few original works. Mostly we borrow and build on ideas and landscapes that have been developed before us. Which is why so much fantasy is so heavily and deadeningly influenced by Tolkien and it’s offspring Dungeons and Dragons.

And I’ll confess – my novel The Princess of Asylum is inspired by Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars and his lost cities. My novels The Luck and The Mermaid’s Tale make use of goblins, orcs, dwarves and giants. I’m not ashamed.

But let’s get back to the The Fall of Atlantis. There are four stories, or perhaps four speculations. Four what ifs?

A Different Greenland – “What if Greenland was never covered by Ice?” This was totally inspired by the radar map of Greenland’s topography under the ice, a topography that showed mountains and valleys, highlands and lowlands, an inner ‘sea.’ The map captivated me. There was a secret geography laid out – how did that work? What kind of lost world was it? How did that inner sea behave, and how did it rule the landscape? The mountains and rivers, high and lowlands told their own story, and within that story, we could populate it with plausible animals, and rewrite the human history. I do my best world building when I have something to work with.

The Fall of Atlantis – “What if Atlantis was a real min-continent in the Atlantic?” I’ll be honest, the stupidest least interesting part of the story, is Atlantis sinking. That’s just another clue that Plato is making the whole thing up, once the story finished, he got rid of the evidence. Just in case anyone asked, ‘Oh, it sank!’ Dudes, if even a medium sized Island sank the way Plato said, you’d have a mile high tidal wave rolling over continents. It’s nonsense. For me, what’s interesting is building Atlantis in the first place, mapping out it’s potential geography and geology, populating it with life, building a civilization. What I found interesting was developing Plato’s parable in a different way, chronicling the decline of a local civilisation, the economic decay, the emergence of pandemics, the rise of slavery, and the destruction of a landscape through ecological degradation.

The Retroverse – “What if all those 50’s Sci Fi movies were all real?” It was like putting together a giant jigsaw puzzle, a glorious excursion through all of 50’s and 60’s sci fi, and carefully, patiently exploring its ideas, its images, its tropes. Connecting up that cinematic universe. It’s just fun. It’s very different from Greenland and Atlantis, a different process. That was starting from almost a single point and building everything from there. This was like weaving together a tapestry, the hidden side of a cinematic universe. All those movies we watched were one side – strange fragmentary, disconnected encounters. But the other side is the architecture, the conspiracy theory, what is really going on, as forgotten colonies of Atlantis, ruled by societies of men and women, go to war, and far out in space cold intelligences wait for their chance.

When the Romans Sailed the Atlantic – “How do I get the Ancients to discover the new world?” Turns out it’s harder than it looks. It’s not easy to cross two thousand miles of Atlantic Ocean, particularly with Biremes and Triremes. This was a fun challenge. Not so much world building, since I was starting with the world we knew. This was more like a journey, getting from A to B or Z. It was about trying to develop a pathway, where with one tiny change – coffee plants colonizing the macaronesian islands, we made something happen that didn’t happen in our history. Part of it was the butterfly effect, something as simple as a random bird from West Africa carrying a viable seed in it’s gut a bit further than happened in our history. Part of it was just, tracing a path.

So what does it all come to? These things are fiction, but not really conventional fiction. They’re more like speculative journeys, thought exercises, experiences in world building.

They were fun and interesting to write, and I think that for some people, they’d be fun to read, full of insights into history and geography, a systematic approach to outlining how the world works. Terrific for want to be world builders, and perhaps for people who want insights into how the world works, and perhaps sparking the imagination with the prospect of new civilisations, new adventures, new histories.

So seriously, dear reader, this is about shameless self promotion. Think about picking it up.